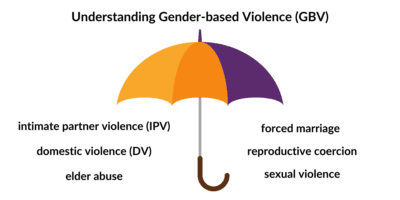

Understanding Gender-based Violence (GBV)

GBV can manifest as physical, financial, psychological, or sexual harm and affects folks of all genders. It stems from disproportionate relationships to power and is more likely to occur in environments that perpetuate alienation, poverty, and disenfranchisement.

The issue is pervasive: it is well-documented that 25% of women and 10% of men have experienced some form of intimate partner violence, a form of GBV.

Studies on gender-based violence remain limited in comparison to the scope of the issue, particularly amongst marginalized populations. The last major study on South Asian women in the United States was conducted in 2003 and reported that two in five South Asian women experienced domestic violence, whereas one in three women were reported to experience such violence within the general population. Since then, the field of women’s rights has evolved and expanded to recognize both gender and violence with greater nuance, but studies on specific populations, such as South Asians, remain extremely limited. While research remains limited, studies also suggest that GBV is experienced at higher rates amongst transgender people.

Gender-based and interpersonal violence can manifest in many ways.

GBV can look like:

- Physical violence: when a person hurts or tries to hurt a partner by hitting, threatening with a weapon, breaking items around you, kicking, or using another type of physical force and intimidation. Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is also a form of gender-based violence.

- Sexual violence: forcing or attempting to force a person to take part in any sex act, sexual touching, or a non-physical sexual event (e.g., sexting) when the partner does not or cannot consent.

- Stalking: a pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact by a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim. Stalking can include unwanted emails, texts, following, contact, and more.

- Financial abuse: Financial abuse can take many forms, including controlling a survivor’s financial resources, income, work hours etc. It can also include withholding and/or controlling money to the detriment of a child and/or destroying someone’s credit. 99% of domestic violence survivors experience financial abuse. Financial insecurity is one of the major reasons survivors of domestic violence stay or return to their abusers. On average it takes a survivor 7 attempts to permanently leave an abusive situation.

- Psychological aggression: is the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to harm another person mentally or emotionally and/or to exert control over another person. Psychological abuse can include: isolation, manipulation, gaslighting, purposefully misgendering, shaming, yelling, name-calling, threats, etc. Neglect and abandonment are also forms of violence.

- Forced Marriage: Forced marriage refers to a marriage in which at least one person did not consent to the union. Tactics such as fear, guilt, fraud, or shaming are often used to coerce a person into marriage. Dowry deaths, honor killings or threats are also forms of gender-based violence.

- Reproductive Coercion: forcing or attempting to force a person to try for a pregnancy, abort or keep a pregnancy, and controlling one’s access to contraception and birth control.

- Sexual harassment: Sexual harassment is a form of gender discrimination. It is covered by federal, state, and local laws. Quid pro quo harassment generally refers to situations in which an employer or supervisor has offered to trade an employment benefit for a sexual favor. A hostile work environment refers to sexual or gender-based harassment that can create an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment, or interfere with one’s job performance.

Violence isn’t always an obvious thing for us to name.

In a youth survivors’ group, a Sakhi once advocate opened a session asking: “What is violence?” One of the participants offered a salient lens that we reference often: violence is “the removal of choice.”

At Sakhi, we often reference the Power and Control Wheel to interpret when and how violence may occur in a relationship.

The wheel shows us how violence can show up in ways that are difficult to pinpoint. When we add together instances of abuse, we begin to see larger patterns of how the exertion of power and control over another person can manifest as violence.

At Sakhi, we seek to translate the vision of a violence-free New York City into cultural and linguistic contexts.

We believe in a violence-free future and engage community stakeholders and partners to help unite the movement to end gender-based violence.

We see a collective imperative to support all persons involved in incidents of GBV, enabling opportunities for those who have experienced harm to escape and heal from it. It may not be possible to end violence, but it is possible to equip individuals with the knowledge and resources to navigate their own emotions and material surroundings. We believe that, if such tools are made accessible and widespread, we can mitigate the occurrence of GBV by furthering an ethos that encourages folks to find power with others rather than a dominating power over others.

Do you live with someone whom you know or suspect is harming you or someone you know? Learn more about creating your own Safety Plan here.

Sakhi helpline: 212-868-6741 (Monday-Friday, 10am – 10pm).